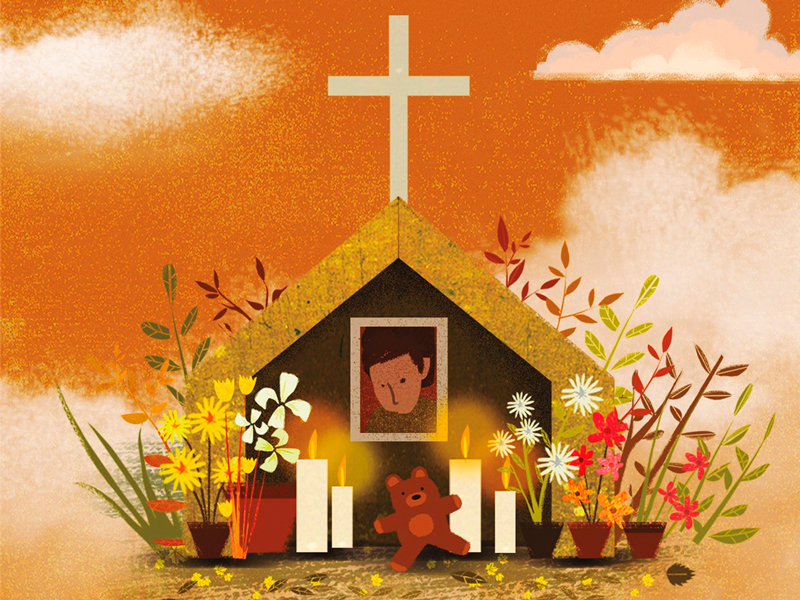

Veneration of the dead is part of the popular culture of many countries in Latin America and elsewhere, but the animitas commonly seen in Chile, principally on roadsides, are a sign that the country continues to pay homage to those who die violently.

In 1995, when the National Library in Santiago mounted the exhibition “The Faith of the People”, the head of the Oral Literature Archive at that time, Micaela Navarrete, decided to illustrate popular devotion by installing wooden structures with tin ceilings, reminiscent of animitas, with jars of dried flowers and a metal tray on which to place lighted candles.

“The surprising thing was that people crossed themselves without asking if someone had died. They did it just for a soul. And not only that: many began lighting candles under the astonished gaze of the guards. We had to wait for them to leave before putting them out...That shows what an animita evokes,” Navarrete recalls.

Mediators before God

“God is further away; that’s why these mediators exist,” says Micaela Navarrete. “The animitas fulfill that function. A one-to-one dialogue between the pious person, who asks for help, and the deceased.”

According to Dr. Claudia Lira, an academic, the animita is a symbolic product of Chilean culture. “It not only fulfills the role of anchoring the soul in pain (as a result of violent death) and soothing it, but also functions as the materialization of mourning. It is the place to which the bereaved return to find the last breath of the loved one, again remembering and honoring that person. They return to take away the pain so [the deceased] can rest in peace,” she says.

The popular belief is that, if a person dies tragically, that person is redeemed, the soul is purified and the deceased becomes an intermediary before God. This applies even to the worst criminals. The famous murderer known as the Jackal of Nahueltoro, who was condemned to death and executed by a firing squad in 1963, also has an animita where many people go to pray and give thanks for favors granted.

There is a belief, explains Claudia Lira, that when someone dies unexpectedly and violently, without justice for the taking of their life, they cannot rest and wander in sorrow around the place of death, appearing and, even, scaring others.

The animita as an object serves as the new body as well as being a shrine and place of prayer. “The prayers fulfill the function of cleansing the soul, helping it to purge that for which it did not have time to repent and, at the same time, purging the pain of death itself, the suffering it experienced that does not allow it to rest,” says Lira.