The sun blazes down on a basketball pitch where some children are playing. They are all very small and in uniform. The boys wear a tie and the girls' hair is kept tidily in place by slides.

"I'm playing with my friends on the pitch, which is also our yard. We always end up playing singing and dancing games with the lay priests who wear huge, long cassocks; with them, we sing songs in French. In French! And under this implacable sun, but I was born here, it doesn't hurt me. Every day, we have this beautiful sun."

That is the scene which María Moscoso recalls, as if it was yesterday. As if she was still far from reaching her 67 years of age.

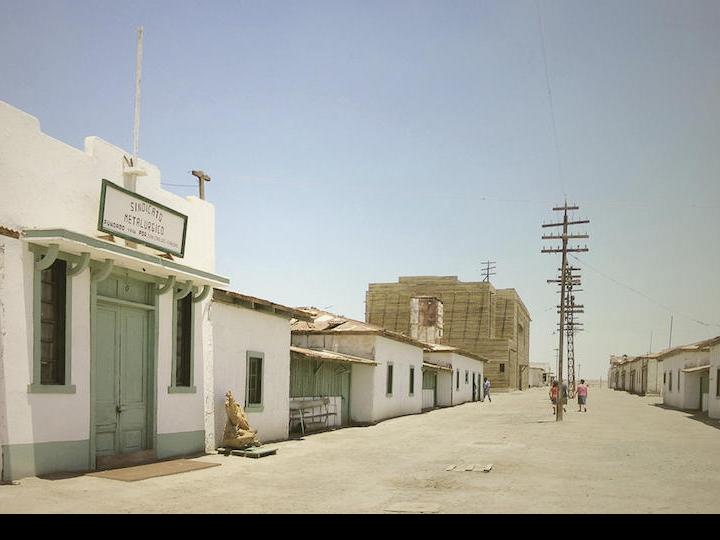

The setting is the San Mauricio School in the Humberstone saltpeter town where María was born and lived for the first 12 years of her life. She has the best memories of those years. "Unforgettable," she says. That is why she is happy that Humberstone and Santa Laura have been declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.

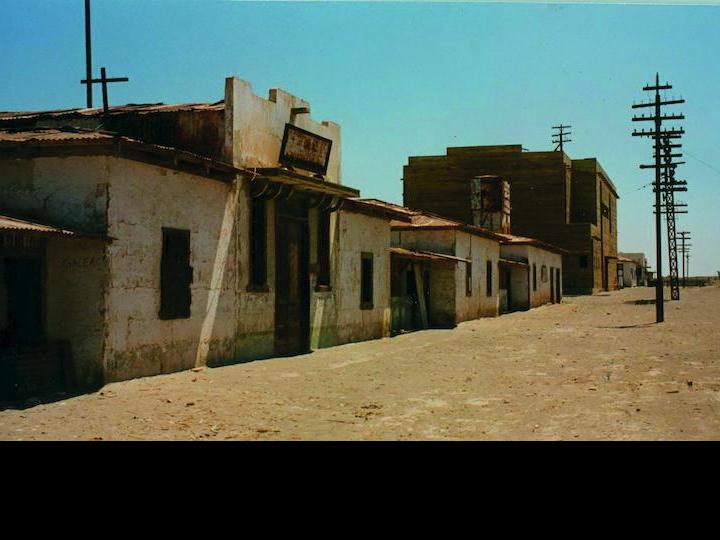

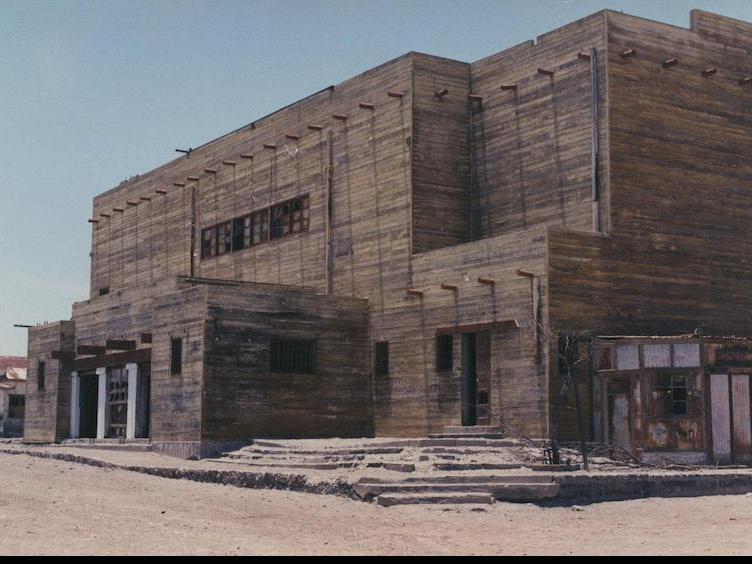

Santa Laura had 425 inhabitants while Humberstone had 3,500. This was the time of the so-called saltpeter cycle (1830-1930) when large numbers of men and women moved to the north of Chile to work in the mining industry. During the saltpeter boom, there were 118 saltpeter towns and 46,470 workers in the pampa of the Atacama Desert. Because of the isolation, the camps where they lived became little cities, with housing and basic services for the workers.

But life there was hard. Shifts lasted over 12 hours and the workers lived in cramped and precarious conditions without sanitation.

Wages were paid in fichas (tokens) that could only be used at shops in the saltpeter towns where the company controlled what was sold and the price.

Until the 1920s, the workers were at the mercy of the saltpeter companies. It was the resulting strikes across northern Chile that prompted the introduction of the country's first social laws.