There was once a train that wound its way through thick woods and the giant leaves of the native nalca plant: a verdant landscape that could be enjoyed without haste because, typically of all old railways, the train was characterized precisely by its leisurely pace.

This part of the heritage of the magic Chiloé Archipelago, off southern Chile, had practically been forgotten, but is now being given a new lease of life as a National Monument.

Inspiration of writers

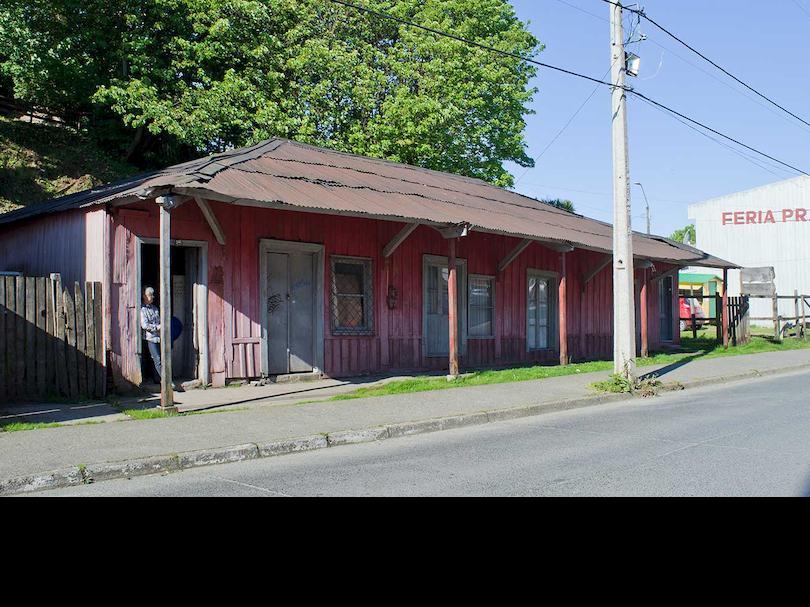

Between 1912 and 1960, the railway stretched 88.4 kilometers between Ancud and Castro, the two principal cities on the archipelago's main island, and also included an 8.4-kilometer branch line from Ancud to Lechagua, its last stop to the north.

In all, there were ten stations: Ancud, Pupelde, Coquiao, Puntra, Butalcura, Mocopulli, Pid-Pid, Castro, Piruquina and Llau Llao.

The railway's construction began in February 1909 during the government of President Pedro Montt Montt and was inaugurated under that of President Ramón Barros Luco.

Before the railway, there was a road between Castro and Ancud but, according to Felipe Montiel, coordinator of the Advisory Commission of the Council for National Monuments in the Chiloé Province, the only really practical alternative for the islanders was to make the journey by sea.

The railway originally had five steam engines of different sizes (to which a locomotive system was subsequently added). It was used to transport both passengers and freight and, in its latter years, was key for the development of the forestry and cattle farming industries. The journey initially took five hours.

"Its slowness was the subject of anecdotes and jokes and it is remembered that, in some places such as the Butalcura incline, the passengers had to get out and push train. It is said that, on one occasion, an old lady was walking alongside the track and the driver, being friendly, offered to take her but she replied, 'don't worry, sir, I'm in a hurry'," reports Felipe Montiel.

The train also served as inspiration for writers, including Neruda, says Montiel. In a letter to the writer Rubén Azócar in 1925, Neruda alludes poetically to the train.

An iron battle horse

The massive 1960 earthquake in southern Chile did significant damage in Chiloé and marked the death of its railway service. It stopped working, but was never forgotten by the islanders.

By linking the island's two main cities in just a few hours, it reduced the internal isolation to which they were accustomed, explains Montiel. From his standpoint, protection of the vestiges of the railway represents a new opportunity for Chiloé, different from its better-known churches, which are today a World Heritage Site.

The recovery of part of the railway history of Chiloé is a way to preserve an important aspect of the development of its people. It serves as a reminder of a time when the archipelago's inhabitants traveled to the saltpeter towns of northern Chile and to Patagonia in Argentina and Chile in search of a livelihood for their families.